The dream of making the world a global village has long been realized through leaps in information and communications technology.

Social media have played a key role in this transformation and this is especially true in Kenya where millions of people visit Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp every day.

Some people view social media as a good thing: it enables freedom of expression and allows new voices to be heard. Others, however, see something evil in social media since people can hide behind anonymity and say whatever is on their minds. In the worst case, social media can lead to incitement and upend governments or even countries.

With less than three days remaining for Kenyans to go to the polls, a social media research project supported by the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) and carried out by the Aga Khan Graduate School of Media and Communications (GSMC) revealed that Kenyans have been spewing insults at each other on social media channels such as Twitter. Although the project cannot monitor private Facebook pages or WhatsApp, it seems that conversations on those platforms can veer into even more dangerous territory. The National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC) is currently investigating several politicians for incitement on those platforms.

“Kenyans are talking hotly on social media. What they are forgetting is that you cannot just talk without taking responsibility. There are limitations,” said Noah Miller, the Managing Director of Sochin Limited and a consultant for the GSMC social media monitoring project. The remarks were given at a roundtable on incitement, dangerous speech, and advocacy held at the GSMC last Wednesday.

In a presentation entitled Incitement “Rights and Response in Social Media & Beyond”, it became clear that Kenyans are hiding behind their computer and phone screens to unleash ethnic slurs and hate speech against each other.

According to the NCIC Act of 2008, Section 13, a person is guilty of hate speech if that person: uses, produces, publishes or distributes content that contains threatening, abusive or insulting words, visual images or behavior; with the intention, or that may likely lead, to stirring up of ethnic hatred or ethnic hatred means hatred against a group of persons defined as by references to color, nationality, and ethnic national origins.

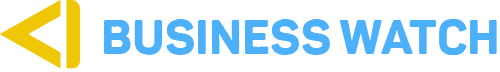

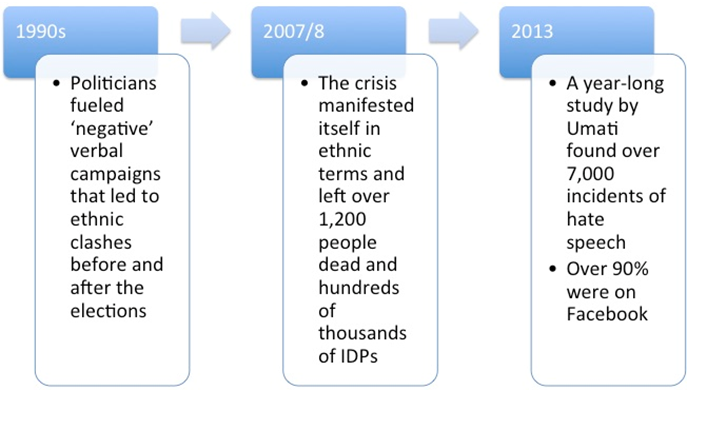

Hate speech is often defined according to the socio-cultural and historical context of a country. Moreover, it is further classified into different categories by organizations such as the Elections Observations Group (ELOG), Umati, and Article 19 as shown in the image below:

“The main challenge is that cases of hate speech are probably underrepresented and under reported due to challenges inherent in monitoring,” said Mr. Noah Miller. “People often use social media to amplify what is happening in the offline world,” he added.

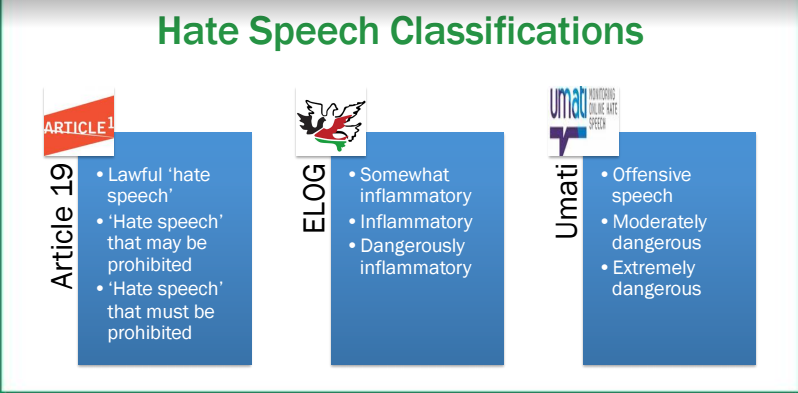

A total of 1.7 million impressions were generated by the 305 posts that were explicit hate messages. However, the research revealed a larger discussion related to the hate topic which generated a total of 134.4 million impressions. The larger discussion included social media chatter around the #WhatsAppAdmin topic, media coverage of politicians alleging committing incitement or being detained for hate speech, as well as posts that had an ethnic dimension around the posting of returning officers.

The research by GSMC, however, did not capture much of the hate-mongering perpetrated on personal Facebook accounts as well as WhatsApp. According to the NCIC, a lot of hate by Kenyans is on Facebook and WhatsApp groups and the commission has identified 20 Facebook groups for being engines of hate-mongering across the country. The commission also said that it had identified specific WhatsApp groups that were spewing hate and assured the public that it was going for the WhatsApp group admins.